Black parents of trans kids speak to the power of public support

“You can’t let your child wait till they’re 40 to breathe. My child needs to be who they are to be comfortable in her own skin.”

Get to Know These 15 LGBTQIA2S+-Owned Beauty Brands

Beauty means so much to queer and trans folks — it is affirmation, it is visibility and, often, it brings out the truest version of ourselves. LGBTQIA2S+ communities are not to be bought; solidarity is not a monthly obligation and support for our communities goes beyond June.

One Year After #BlackoutTuesday, Have White “Allies” Actually Kept Their Promises?

White where we left off: looking back at the day Instagram turned black and what brands and influencers have — or haven’t — done for Black lives since June.

R29Unbothered continues its look at Black culture’s tangled history of Black identity, beauty, and contributions to the culture. In 2021, we're giving wings to our roots, learning and unlearning our stories, and celebrating where Black past, present and future meet.

Six years after the world watched Eric Garner yell, “I can’t breathe'' 11 times while police were killing him, we heard George Floyd scream the same sentence 28 times before his life was taken. This was shortly after Ahmaud Arbery was gunned down in Georgia and mere days before Regis Korchinski-Paquet would fall to her death off her apartment balcony in the presence of Toronto police.

The string of videos and incidents of police brutality against Black people in the summer of 2020 was devastating. Our community was under attack once again, and while our resilience and uprising was expected, the response from non-Black people was something new. Companies, brands, influencers, and corporations that weren’t committed to fighting anti-Black racism prior to George Floyd’s killing were suddenly releasing Black Lives Matter statements. When I was an organizer with BLM Toronto, I remember the years where the media couldn’t even wrap their mind around saying “anti-Black” on camera. I remember when saying “Black Lives Matter” was a controversial statement, one organizers and activists like me had to defend over and over. But by June, non-Black people were cashing in their ally cookies just for saying they believe Black people deserve justice and life. Store fronts had signs in their windows. Homes were adorned with BLM flags. On any given morning, I would see at least five people on my morning commute wearing buttons plastered with the mantra calling for Black liberation.

But the most egregious and public display of this collective “call to action” was #BlackoutTuesday on June 2, 2020. Music executives Jamila Thomas and Brianna Agyemang set out to disrupt “the long-standing racism and inequality that exists from the boardroom to the boulevard.” The pair initially created the hashtag #TheShowMustBePaused but it was eclipsed by #BlackoutTuesday, which spread widely. Even in supposed allyship, Black women’s voices are erased. In just a few hours, more than 14.6 million black squares flooded Instagram feeds as real commitment and calls to action were replaced with a hollow social media trend.

Within days of George Floyd’s public lynching, more than 950 brands,* companies, influencers and retailers rushed to release statements of solidarity in the form of a literal black square. Searches for “blackout Tuesday image” and “blackout image” surged 400 percent within the same day. Let’s be clear, social media trends will not save us from police brutality. After all, in the two weeks after George Floyd’s killing, protestors were subjected to even more brutality. While dozens were injured or shot by police, journalists were also attacked over 140 times by the police between May and June. While some brands and influencers have been trying — and some not hard at all — to read the room and do their part to address anti-Black racism both internally and in society, reactionary corporate diversity and inclusion measurements will not eradicate anti-Black racism in all its violent forms.

I spent the last year facilitating dozens of anti-racism training sessions and screaming about the triviality of trends like posting black squares. There’s no doubt social media can have beneficial impacts on movements. From the Arab Spring Uprising to the #MeTooMovement, studies suggest that those who engage with politics online also do so in their daily lives. However, #BlackoutTuesday created real dangers to activists and Black liberation organizers on the frontlines. This method of “allyship” begs the question: what does this actually solve? Often, it absolves non-Black people from taking action against systemic inequalities and addressing how they benefit from anti-Blackness. Instead, they wear badges of “wokeness” to present an image to their audiences. It’s been eight months since #BlackoutTuesday, and in the aftermath of the summer of protest, it’s time to take stock of who has stood by their pledges and committed to real change and who just showcased performative allyship.

White celebrities like Megan Fox, Courteney Cox, and Jennifer Love Hewitt all participated in #BlackoutTuesday by posting “Black Lives Matter,” the #BlackoutTuesday hashtag, a black square, and little else. Famous influencers like Dixie D’Amelio, Zara McDermott, and Georgia Steel did the same. As I watched celebrities use our community’s pain for likes and comments, it seemed clear to me that these minimal posts on #BlackoutTuesday and the days after revealed that — at least publicly — their activism and empathy begins and ends on social media.

Other influencers were more critical of the black square approach. Actress and writer Natasha Negovanlis, who has over 160 thousand followers, participated in #BlackoutTuesday but left out the empty square and hashtag instead opting for a call to action for fellow white people. “Taking a pause from sharing my own content, without announcing that I would be muting myself, and instead reposting Black voices, felt like a better use of my platform at the time,” she says over email. “I think before hopping on any social justice hashtag it’s important to research its origins and listen to the people it’s meant to be helping.”

Negovanlis recognizes the “ally card” is one that is consistently up for renewal and that dismantling anti-Black racism happens in the small steps that lead to bigger systemic changes. “I moved towards sharing book suggestions by Black writers, reposting Black voices, and promoting Black businesses. I also used the YouTube Live show I was producing at the time, a virtual fan convention I attended, and sales from my merch, to raise money for smaller, Black owned non-profit organizations in my own city like FoodShare Toronto, Adornment Stories, and Obsidian Theatre Company.”

Negovanlis’s actions show how influencers can responsibly use their large platforms to address anti-Black racism beyond one day of action. Non-Black people trying to convince the world they are anti-racist without leading and living an anti-racist life is just vanity. In moments of urgency especially, influencers should be handing off their social media platforms to organizers and activists who are on the frontlines calling for change. Selena Gomez and Lady Gaga also did this last year. In doing so, they demonstrated it’s okay to admit there are more qualified voices that should be given the mic.

The most frustrating part of #BlackoutTuesday was watching brands, especially those that rely on Black consumers stay glaringly silent throughout the day. Fashion Nova was particularly called out many times for their absence in the conversation for hours. They participated in the day after mounds of public pressure and have since released statements disclosing their donations to the Know Your Rights Camps, Black Lives Matter and the NAACP Defense and Education funds. While donating to movements and organizations is necessary, anti-Black racism is not a problem that will go away by solely throwing money at it. In announcing their donations, Fashion Nova stated, “our actions speak louder than our words.” In the months since this announcement, it doesn’t seem they have continued their words, let alone actions. If you glance at Fashion Nova’s Instagram account and its over 500 pictures since June 2, there hasn’t been a single mention of anti-Black racism. Their senior executive team seemingly also does not include any Black people.

Fashion Nova is a brand that relies on the Black woman’s dollar, and consistently profits from our support as consumers and cultural brand ambassadors. After all, Cardi B’s 2019 collaboration with the fashion brand made $1 million USD in 24 hours, while Megan Thee Stallion’s line made $1.2 million USD in 24 hours. We are their target market, but the brand seemingly can’t be bothered to represent us in all our plurality. Their popularity has hinged on using Black celebrities or curvier models who reflect diverse body types, but they’re still mostly selling one (read: light) kind of Blackness. Profiting off of Black women’s bodies without addressing the systems that violate our bodies is inherently part of the problem. There’s something to be said about a company that has not publicly shared anything related to Black Lives Matter in eight months while they make millions off our communities. Even if there is groundbreaking work happening to address anti-Blackness behind the scenes, why have they not made that transparent to their consumers? From the outside, it looks like just another case of wanting to capitalize on Blackness until it’s time to show up for Black people. Fashion Nova did not respond to our request for comment.

Brands like FashionNova can take leadership from Deciem, The Abnormal Beauty Company (most known for their ‘The Ordinary’ line). They launched their “Beauty is Using Your Voice” campaign just before #BlackoutTuesday in the midst of the summer’s protests occurring across North America. Since then, they’ve continued collaborating and donating to local Black grassroots projects. “We committed to doing better and knew this movement was not just a moment, but a time for meaningful and impactful change,” CEO and co-founder Nicola Kilner told me over email. The company offers their teams paid days off to read, learn, listen, educate themselves and join protests if they wish. They’ve created a diversity and inclusion board to give employees direct access for feedback and discussion to senior leadership. They have also committed to being more intentional in their hiring practices and succession planning to increase the number of Black voices within their leadership. Their team is admittedly quite diverse but Kilner recognizes, “we can and must do better in our senior positions.”

These efforts are a start, and companies committing to improve their hiring practices is a beneficial step. Leadership representation and hiring practices were amongst the biggest takeaways from #BlackoutTuesday. In fact, Uoma beauty brand CEO Sharon Shuter created the #PullUporShutUp challenge in response to #BlackoutTuesday to challenge brands and companies to publicize their senior leadership and give consumers a glimpse how many Black people are around the table. It is important to note, however, that anti-Blackness is a pervasive issue that will not magically disappear by hiring a few token Black employees, even at the leadership level. Additionally, the Black people in these organizations aren’t just dealing with racism within the workplace, they’re dealing with it with their everyday lives. These companies’ advocacy towards removing anti-Black racism has to extend after employees leave the workplace.

The most promising commitments from #BlackoutTuesday are the ones that occurred prior to June 2 and continued after. Sephora is one of a handful of companies that did this. In fairness, they kind of had to. The beauty giant has come under fire many times over the last few years for racism in its stores including most notably with R&B singer SZA publicly detailing being surveilled in the store. This sparked a series of diversity training and the genesis of the Racial Bias in Retail Study. Last month, they released the report, and unsurprisingly, it disclosed Black retail shoppers are twice as likely to receive unfair treatment. The report also included a five-point action plan. The most potentially impactful detail: the company has committed to reducing the presence of third-party security vendors in stores with the goal of minimizing shoppers’ concerns of policing. In the report, President and CEO Jean-André Rougeot admitted, "At Sephora, diversity, equality, and inclusion have been our core values since we launched... but the reality is that shoppers at Sephora, and in U.S. retail more broadly, are not always treated fairly and consistently.”

Former Sephora manager, *Maria is not as hopeful, “This is a big area of opportunity for their development but working there for seven years taught me what you see and what they try to portray as a company is not necessarily the reality.” She notes despite the diversity and inclusion image, racial biases embedded in Sephora are deep rooted. This could be a result of a leadership team that does not represent the consumers.

The company is one of many participating in the 15 Percent Pledge, a campaign founded by fashion designer Aurora James in the midst of the global uprisings, calling on retailers to dedicate 15 percent of their shelves to Black-owned businesses. Still, the company has a long way to go. Sephora stated, “when we committed to the 15 Percent Pledge in June 2020 we had eight Black-owned brands...this year we are working toward doubling our assortment.” Other major retailers including, Macy’s, Indigo, and West Elm have all also taken the pledge.

These pledges are promising but still speak to the general frustration I’ve felt since #BlackoutTuesday. The question that has floated through my mind consistently since last summer is what took so long? It’s hard to find the words to describe what it has felt like to see the world suddenly “care” about Black people and anti-Black racism.

On one hand, it’s been inspiring to see thousands flood the streets and take back our collective power. We’ve seen activists using the momentum to continue pushing against state-sanctioned violence. People finally know what “Defund The Police” means, allowing for massive leaps in conversations around reallocating public funds to social services. But #BlackoutTuesday also felt like one, big, painful slap in the face. After all, we’ve seen the same pattern again and again: A tragic event takes place, non-Black people feign shock, release empty statements, make donations, and maybe, maybe post some resources and then they’re right back to radio silence. The status quo can be debilitating.

These recent efforts by certain brands and influencers point to slow incremental change, but I can’t help but shake the feeling that it should never have come to this. What if we thought about dismantling anti-Black racism less as a checklist with items to tick off and more so as an ideological shift in our society’s framework? What if we saw these same brands and companies care about us just as much while we are alive as when we become a hashtag? What if Black people weren’t the only ones responsible for this work?

Ultimately, we know Black liberation will cost. Even with the best intentions and best outcomes, there is always more that can be done to uplift Black people and create systemic change. It will take more than statements, donations and social media hashtags to uproot our current systems. It will take a release and then a redistribution of power. It will take collective responsibility and an eagerness to embody solidarity rather than just performing it. So the question remains: how much are those with power willing to give up?

*Editor's note: Refinery29 blacked out its homepage on June 2, 2020, which prompted backlash from former and current Black employees who said they experienced racially-motivated micro aggressions and toxicity at the company. In response, the brand’s Global Editor in Chief stepped down, and the parent company, Vice Media Group, committed to various diversity, equity, and inclusion initiatives to address the reported problems.

We've republished this piece in light of the first anniversary of George Floyd's death. This piece was originally published on February 9, 2021.

*Name has been changed for privacy.

Emancipation Day 2020: 3 Black Youth On Their Canadian Heroes

August 1 marks the abolition of the enslavement in British colonies, including Canada. Here, three Canadians explain what the day means to them.

Marking Emancipation Day 2020 will be a very different experience from years past. With the backdrop of simultaneous public health crises—the COVID-19 pandemic, and ongoing police violence—we’re forced to recognize this momentous occasion without whining our waists in the Caribana parade, and the many other celebrations we’re used to attending have all gone virtual. But August 1 is crucial to understanding Canadian history, particularly at a moment when so many Black people are pushing to fully experience the freedom our ancestors fought for.

Emancipation Day marks the abolishment of the enslavement of African peoples in all British colonies worldwide. Countries such as Barbados, Jamaica and Grenada have been marking it for decades, but in Canada it was only formally recognized in Ontario in 2008. It took another decade for it to be marked across the country.

The legacies of slavery—and resistance—in Canada are often forgotten. Three Black youth and community organizers describe what Emancipation Day means to them and how they are continuing the legacy of Black liberation resistance.

Victoria Rodney, (she/they), 22, Community Builder with ACB Network; Waterloo, Ont.

What does Emancipation Day mean to you?

I think the most important part to remember is, this history, this fight that’s been occurring, is not one that’s so far away. We may not think about this day and the significance in our daily lives, but Emancipation Day is a reminder of everything we have done and everything we can do. Back home in Jamaica, we celebrate by rocking our flag colours. You can’t go out in the streets without seeing everyone head-to-toe in green, yellow and black. Here in Canada, typically, I honour this day this year by participating with Sing Our Own Song, an intergenerational singing group. That’s not possible this year, but I’m still going to find time to connect with the land and celebrate our past [as well as] the future we want.

Who is one of your Black liberation Canadian heroes?

I would have to say Mary Bibb. Not only was she an educator and one of the first Black journalists in Canada, she was also a fierce abolitionist. She was actively involved in ensuring Black people escaping slavery in the 1850s had protection and safety free from enslavement: she ran both a school and a publication, The Voice of the Fugitive. She is one of the prime examples that Black women in particular have been doing this work. She really paved the way for me and you as journalists and organizers.

How do you see yourself continuing the legacy of Black resistance in Canada?

I honour this legacy every day by existing in my queerness, in my Blackness, unapologetically. Just being in those intersections I know honours all they have fought for. My work both at the University of Waterloo campus and off is centred around making sure Black students and the community feel safe and know that someone has their back. My liberatory work has included campaigns against white supremacy on our campus and opening up RAISE, the first space for Black, racialized and Indigenous students.

Timiro Mohamed (she/her) 22, Youth Poet Laureate; Edmonton

What does Emancipation Day mean to you?

I only learned about Emancipation Day recently. It speaks to the erasure Black people face within this country. I’ve always known about Juneteenth and what abolition of slavery in the U.S looked like, but never even known about my people here. And this is so important for us to know about these things, it’s vital for me as someone in the diaspora to understand Black Canadian resistance.

Who is one of your Black liberation Canadian heroes?

For me, it has to be Viola Desmond [the civil rights-era businesswoman on the $10 bill]. Though we know her story and what she overcame, what sticks with me the most, she had no intention of being an activist or freedom fighter. The sheer nature of just existing as a Black person, a Black woman particularly, means she’s thrown into fighting for civil rights to demand the dignity she’s not receiving for herself and her communities. That’s the story for so many of us: We may not have intentions to dive into activism but feel there is no other choice.

How do you see yourself continuing the legacy of Black resistance in Canada?

It’s such an honour to organize in this country and follow the footsteps of those who’ve come before me. Though, there are still moments I do feel pessimistic in thinking, “I can’t believe we still have to fight,” but I know this fight has to continue. People before me have done their part and I have to as well.

Aisha Abawajy (she/her), 22, Community Organizer with Araari Ampire, Halifax

What does Emancipation Day mean to you?

It’s so important for us to recognize how far we’ve come and how far we still have to go. Black people have been fighting for so long and we will continue to do so until we see Black liberation. We fight within the boardrooms, the classrooms, in hospitals and in the streets.

Who is one of your Black liberation Canadian heroes?

Lynn Jones, an African Nova Scotian powerhouse [and leader, union activist and community organizer]. The most impactful thing about her is truly her heart. As a young person in Halifax, she validates me so much and the work I do. She sees me and other young Black organizers and that is the most beautiful part, she sees us.

How do you see yourself continuing the legacy of Black resistance in Canada?

By living my best life, my authentic self fulfills the dreams of ancestors that fought for me. I could not be here without the love and activism of so many unsung and unknown heroes and queer Black women in particular who have held it down. Years from now, even if I transcend to one of those unknown heroes as well, if Black people are able to live their best life as well, I know I’ve done my part.

Five Black queer activists to celebrate beyond Black History Month

Because the celebration shouldn’t stop when February ends

It’s February: our annual anthem “I’m Black Ya’ll” is playing non-stop. We’ve pulled out our best coloured hair, dookie braids and locs and we’re celebrating our beautiful melanin for Black History Month.

But this revelry need not end in February. Rather, it should persist throughout the year.

That’s why we’ve profiled five Black queer and trans activists — the folks who too often get left out of our collective celebrations of Blackness. It’s a reminder to celebrate their lives and work not just this February, but every month.

OmiSoore Dryden

Role: Incoming James Robinson Johnston Chair in Black Canadian Studies at Dalhousie University’s Faculty of Medicine

Pronouns: She/her

City: Toronto, ON

Who is OmiSoore?

“I earned my PhD in social justice education from the Ontario Institute for the Study of Education and the University of Toronto. My dissertation examined how blood donation rules discriminate against queer and trans populations, and particularly examined how Black people are impacted by it.”

What are you most proud of in your activism?

“I am proud of sharing activist practice with my nephew, [by] taking him to protests and community and planning meetings. Together, we share stories and ideas and hopes and dreams.”

What quote do you live by?

“Audre Lorde’s quote, from Sister Outsider: ‘It is axiomatic that if we do not define ourselves for ourselves, we will be defined by others — for their use and to our detriment.’ This quote has guided me through many difficult, traumatizing and dreadful moments. It brings me peace.”

What does Black liberation look like for you?

“It is when we live our full selves in community with one another. It is a vibrant anti-colonial practice that supports us in living (through our contradictions) in the fullness of our freedom. We make community outside of, beyond and against current colonial systems and practices. We practise real restorative justice. We engage in vibrant, outrageous, always consensual sexual freedoms. And we always always stand against injustice — regardless of the uniform it wears, or how comfortable it may feel.”

Nasra Adem

Role: Multidisciplinary artist

Pronouns: They/them

City: Edmonton, AB

What they do

“I curate spaces for creatives living at multiple intersections, with a current focus on queer Black femmes. My main focus for the last three years has been curating Black Arts Matter, the annual Black arts festival that brings local, national and international poets, dancers, musicians, visual artists, academics, healers and other Black creatives together in the spirit of joy and collective healing.

“I founded this festival out of a need for Black-centred creative spaces in Alberta. As an actor, writer and mover, I was often met with the myth that Black artists aren’t here or of a professional calibre. This was especially dismembering because I was saturated in my community’s organic way of relating to art 24/7. I knew we were here, and have been here, to create and cultivate culture the way Black people do wherever we are.”

What are you most proud of in your activism?

“What’s been the most beautiful thing to see is my community — the people I pour my love and time and dedication into — grow into themselves and their unique light. Whether it be youth I work with or big homies, it feels so good to see how my curiosity about human beings and what makes us divine challenges others to see themselves in a more nuanced, compassionate way.

“I love people. I love Black queer people. And we’re made up of so much. I’m proud to know I’m working to be curious about us, listen to us and believe us so the world can learn to do the same.”

What does Black liberation look like to you:

“We must rest and use our creative magic for means other than survival and resistance. I want us to remember how to use our whole lungs and be less reactive and more intentional. I want us to determine the pace and value of our lives and times outside of capitalism. Black liberation looks like wild joy and a reimagining, remembering and reclaiming of the rituals that have always kept us alive.”

Yamikani Msosa

Role: Grassroots feminist organizer, frontline worker, consultant, educator and yoga instructor

Pronouns: She/they

City: Toronto, ON

Who is Yamikani?

“I was born in Lilongwe, Malawi, and was raised in Ottawa. I’m a queer Black femme with invisible disabilities. I’m also a member of Brown Girls Yoga Collective, and in 2017 I founded a SEEDS, a yoga class specifically designed for survivors, victims and those affected by sexual trauma and gender-based violence.”

What does Black liberation look like for you?

“Recently, I held a yoga class for Black survivors and people affected by sexual violence. As someone who has supported survivors for the last 10 years, I know there are very few spaces that they are able to breathe and talk about their experiences. There were tears, laughter and anger — each person was able to freely express themselves without fear of being judged, misunderstood or having to hold back their counsellors’ feelings of fragility around anti-Black racism.

“I tell you, the power of breath is something else: it’s the first thing that we do when we enter this earth and the last thing that we do when we leave this earth. But for Black people it’s one of the most powerful forms of resistance. And yes, some may say that it’s an odd answer, but think about it.

“When folks I work with, family members and friends share experiences about their trauma from anti-Black racism, homophobia, sexism and transphobia, they share how they often hold their breath in shock, fear or anger.

“Breathing deeply allows us to connect with our bodies and nurture our bodies in the most powerful way. It doesn’t take all the shit of the world away — I don’t want to sound naive or like some clueless wellness human — but it’s the fuel we need to get the work of our ancestors done.”

Douglas Stewart

Role: Self-employed organizational development consultant

Pronouns: He/him

City: Toronto, ON

Who is Douglas?

“I have a long history of commitment to youth development, regularly providing training and organizational development to many youth empowerment agencies.”

What are you most proud of in your activism?

“The most meaningful thing I think I’ve done to date is holding space with Black people in their final hours as they transitioned from this life due to complications from AIDS.

“One case in particular that was especially painful was with a brother from St Lucia, the first person in his family to go to university. He was attending school in the US. He came to visit some family in Canada and he got sick. When he tried to go back to the US, they wouldn’t let him cross the border [because] it was so clear he was sick. He came back to Canada and the state attempted to send him back to St Lucia. Even his family was freaked out, trying to distance themselves. There was so much stigma around that time. He was eventually hospitalized and without a home; he was staying in an industrial house before I took him to Casey House where he passed.

“I remember sitting with him, holding his hand and he asked me, ‘Am I going to die?’ I had no idea what to say; I just ended up answering, ‘What do you think?’ He passed a few days later.”

What does Black liberation look like to you?

“Black liberation is, to quote Nina Simone, ‘freedom from fear.’ I think that’s the life we are all dreaming about: our ability to be our truest forms without fear.”

Courtnay McFarlane

Role: Visual artist, poet and manager of children, youth and adult services at Davenport-Perth Neighbourhood Community Health Centre

Pronouns: He/him

City: Toronto, ON

Who is Courtnay?

“I have been working in the community health sector for many decades addressing the social determinants of health within marginalized communities. I am passionate about addressing the barriers marginalized people face when they are attempting to access health services.

“I am also currently curating an exhibit at Toronto’s BAND Gallery called Legacies in Motion: Black Queer Toronto Archive Project as part of the Myseum Intersections festival 2019. Legacies in Motion seeks to unearth the stories of the vibrant period of political organizing and cultural activism from Black LGBTQ2 communities in Toronto in the 1980s and 1990s.”

What are you most proud of in your activism?

“I was most proud of the roles I played as a founding member of a number of Black queer groups and organizations in the early ’80s and ’90s — such as Zami, Sepia, AYA Men — that provided voice and visibility for Black LGBTQ2 individuals and issues. During those years, we were actively engaged in challenging oppression and discrimination through political activism, as well as the creation of spaces of resistance, affirmation and creative expression. This activism in many ways laid the foundation for events, organizations and movements addressing Black LGBTQ2 communities today.”

What does Black liberation look like to you?

“To paraphrase Nina Simone speaking about freedom, I would say Black Liberation is ‘no fear.’ Black Liberation is the absence of fear and the ability to fully be all of who we are wherever we are.”

Interviews have been edited and condensed for clarity.

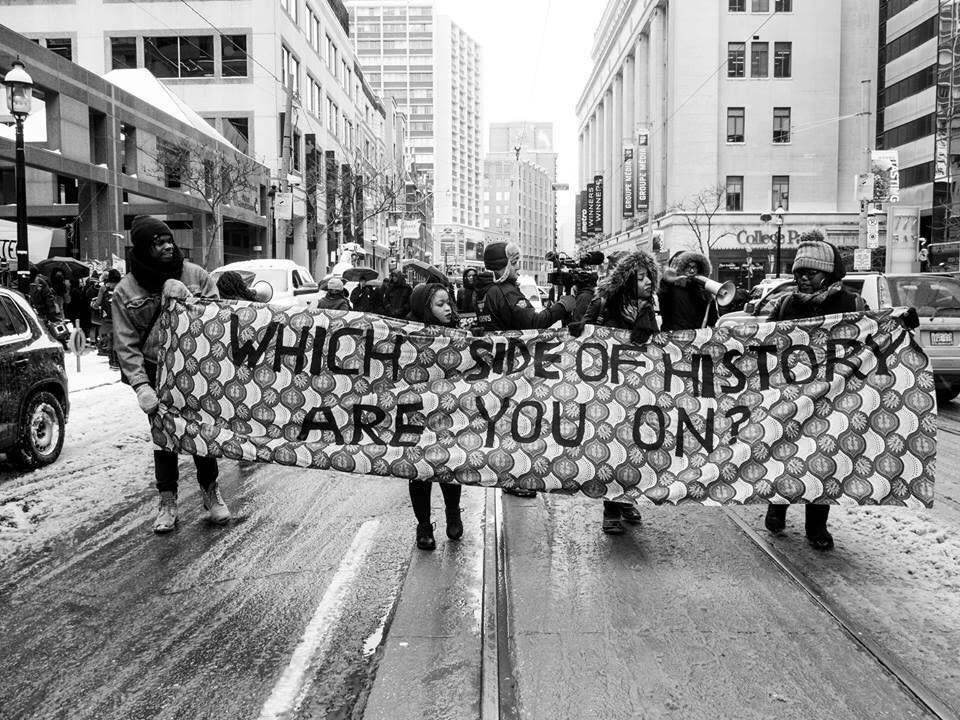

Protesting for Black lives during COVID-19

Black communities have taken to the streets to protest white supremacy during COVID-19 with the knowledge that we can—and will—keep each other safe

We’re currently in the middle of a global uprising. In Canada, organizers and protesters are demanding justice against anti-Black racism from the Yukon to New Brunswick. As national conversations about defunding and abolishing the police evolve, we are forced to reimagine what community safety can look like for us all. These protests have demonstrated what Black communities already know: We can and will keep each other safe.

The harrowing reality is Black people are facing two public health crises simultaneously: the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic and more than 400 years of anti-Black racism. The former was once labelled “the great equalizer,” a public crisis that supposedly affected us all in equal measure—and yet it never has. We saw the urgency in public response when basketball players, the prime minister’s wife and seemingly richer white people contracted the virus. And though much was unknown during the early days of this pandemic, it has become clear that the virus disproportionately affects Black people. In the U.K., studies indicate long-standing disparities in wealth and living arrangements contribute to the fact that Black people in England and Wales are twice as likely to die from COVID-19 as their white counterparts. While this data is from overseas, we can expect the same impact on Black people in Canada. Some early reports reflect this: Experts told Global News, for instance, that Black neighbourhoods in Toronto have been hit hardest by COVID-19, while research into rates of mortality in the U.S. by race and ethnicity have found that Black Americans are dying from the virus at three times the rate of white people.

The COVID-19 pandemic is an indicator of the much larger death sentence Black people continue to face. With the world on pause, we watched George Floyd, a 46-year-old father of five, scream “I can’t breathe” 16 times, read about how 26-year-old D’Andre Campbell was in distress when he called for the police and how the family of 29-year-old Regis Korchinski-Paquet was home while she had an interaction with the police. It’s worth noting that Floyd had contracted COVID-19 prior to his death. His senseless murder is the perfect example of how susceptible Black people are to dying by state-sanctioned violence than they are due to a pandemic.

This uprising has included national demands, creative disruptions and robust health and safety measures. And as protesters take to the streets, Black and Indigenous organizers are ensuring the care and safety of those demonstrating.

In Whitehorse, three mutual aid grassroots groups offered peer-to-peer emotional support to those in need in the days following their rallies and marches, free of cost.

In Ottawa, volunteer emergency responders and CPR-trained individuals arrived on-site in case of medical or mental health emergencies during rallies in the city. Local mosques donated more than 1,000 masks for demonstrators. “We completely relied on our community and they showed up in all ways,” says Vanessa Dorimain, organizer of Ottawa’s March for Black Lives event.

“These protests have demonstrated what Black communities already know: We can and will keep each other safe”

In Toronto, a volunteer initiative called the Bike Brigade, which began as a mutual aid effort to provide food and supplies to those affected by COVID-19, formed a bike barrier that allowed protesters to stage a six-hour sit-in for Not Another Black Life’s Juneteenth demonstration. Outside of Toronto Police headquarters, organizers chalked Xs on the ground to encourage social distancing.

In Fredericton, New Brunswick, organizer Husoni Raymond says Black communities came together to ensure the safety of one another during a demonstration following Floyd’s murder. “Our communities have always taken care of each other and provided to others what they didn’t have.” Raymond adds that the protest was organized in less than 24 hours. “And in that time, coalition partners stayed up to sew masks to ensure we [could] distribute to those who didn’t have any,” Raymond says.

As this revolution continues, we don’t have to recreate new ideas surrounding safety; we can draw inspiration from the ways past and current organizers and community members have been practising collective care:

Wear masks.

Bring hand sanitizer.

Wear eye protection to combat against tear gas tactics used by the police.

Don’t wear contact lenses.

If possible, minimize yelling to avoid spread of droplets; use signage and noisemakers to express your emotions.

Come and leave with a small group.

Have volunteers distribute hand sanitizers and masks to those without.

Use a large open space that encourages physical distancing.

Avoid attending if you feel ill.

Partner with testing centres to prioritize rally participants.

Finally, if you can, try to self isolate for two weeks after possible exposure.

This is a moment of global resistance. Marginalized communities are pushing back and demanding change that will ensure community safety. Even in crisis conditions, we have kept—and will always keep—each other safe.

Remembering the People We Often Forget on December 6

Every year on December 6, government buildings fly their flags half-mast and dozens of memorials are held across the country for the 14 women who were killed in the 1989 mass shooting at Montreal’s École Polytechnique. At each,…

Every year on December 6, government buildings fly their flags half-mast and dozens of memorials are held across the country for the 14 women who were killed in the 1989 mass shooting at Montreal’s École Polytechnique. At each, the names of the victims are read and promises are made for action.

But what about the rest of the year, and the other people whose names we don’t know?

While it’s undoubtedly important to remember the 14 women killed on that day in 1989, it’s also important to acknowledge those who are most at risk for experiencing gender-based violence. Because those women are often the most forgotten—and the ones for whom action isn’t promised.

“Those whose voices are not the most heard in society are the most impacted by violence and in need of service,” confirms Erin Lee, a gender-based violence advocate, survivor and executive director for the Lanark County Interval House in Carleton Place, Ont. “There are layers and layers that act as barriers for us; it’s not one aspect of our identities, it’s the accumulation of every aspect of our identities that make us the most vulnerable.”

Lee was 23 when the Montreal massacre happened, and she remembers the stillness across the country as feminists had to accept, once again, they were not safe—and she realized the need to address gender-based violence was urgent. And so, she’s spent the past 28 years advocating for survivors, but says that little has changed in terms of who is overlooked in the Canadian conversation.

There is perhaps no more vulnerable population in relation to gender-based violence than trans sex workers. Case in point: Moka Dawkins, who is a Black trans woman, and who, earlier this year was found guilty of manslaughter despite testifying that she acted in self defence after a male client (who had three previous convictions for domestic assault) stabbed her in the face. Sentencing for Moka—who was initially placed in a prison for men, where she says she was physically and verbally abused—is now ongoing, while Maggie’s, a Toronto-based organization that advocates for sex workers, provides Moka with support and mobilizes her supporters. “Society says if you are in this profession, if you are trans, you are not worth fighting for,” says Akio Maroon, gender-based violence advocate and former board member for Maggie’s. “It’s a social hierarchy of who is deemed worthy of protection; as sex workers, we are always excluded.”

The media—alongside the justice system and white feminists—plays a major role in determining said hierarchy. Case in point: the phenomenon of “Missing White Woman Syndrome,” coined by the late PBS journalist Gwen Ifil, refers to the disparity in media coverage for missing and murdered Black women compared to their white counterparts. “Women of colour are victimized, they are murdered and they make second page of the newspaper,” says Lee. “By day two they are on page six and after that we don’t hear about them anymore. Black women are even lucky if they make the news.” (For reference, Black women are murdered by men twice as often as white women.)

It’s also important to note that marginalized women and girls are often forsaken by those meant to protect them. From Tina Fontaine—a 15-year-old girl who was murdered in Winnipeg in 2014 despite having had recent contact with police officers and social workers(oh, and the man charged with her murder walked free)—to the dozens of women who have come forward with their experiences of modern-day sterilization, Indigenous women have felt the systemic acts of gender-based violence enacted on their families, bodies and communities for generations. They’re also more than five times more likely to die as the result of violence than non-Indigenous women. “There are thousands of Indigenous women who are missing or murdered,” Lee notes. “Our justice system has failed Indigenous women and communities. Absolutely failed. They have tossed, forgotten, and neglected Indigenous women.”

The discrimination and lack of care faced by marginalized people is compounded for those living with disabilities—research from 2014 shows that Canadian women with disabilities are twice as likely to experience violent crime or sexual assault than those without disabilities—as well as those living in remote or rural areas, where help can take longer to arrive than it does in cities. Through her work in Lanark county, Lee helps many women living in rural areas, and notes that the violence experienced in these regions is often incestual.

“On top of that, we are queer, trans, racialized, and disabled,” says Lee. “[Other people] don’t know why calling the cops isn’t a reality or option for so many. Few recognize all of the layers impacting us and truly know how to assist.” She notes that assistance has to begin with acknowledging marginalized voices and letting them dictate what justice looks like for them.

December 6 is about taking action, it is about remembering, it is about fighting back. It is about looking in the face of patriarchy and resisting. It is about challenging norms and creating truly a more equitable world for us all. It is about reading and knowing the names of the 14 women killed at École Polytechnique—but also the names that are rarely spoken in the news, whose faces and stories are never heard. May we continuously fight for the most marginalized among us, may we never forget them. Not again. Not ever.

I Can’t Stop Thinking About Moms Who Are Separated From Their Families—Like Mine Was

The last memory I have of my homeland is sitting in an airplane, naively excited about the adventure my family was about to have. Five-year-old me looked down at the ocean that encircled my small island and hoped wherever we were going was near the water. But as my mother watched the waves of the ocean, she prayed each tide would close the distance between our family, now split in two.

The last memory I have of my homeland is sitting in an airplane, naively excited about the adventure my family was about to have. Five-year-old me looked down at the ocean that encircled my small island and hoped wherever we were going was near the water. But as my mother watched the waves of the ocean, she prayed each tide would close the distance between our family, now split in two.

Haiti was the only home we’d ever known, but my family’s political activism, particularly my father’s, made us targets within our community. Then, one of the young girls in our neighbourhood was assaulted by rival political groups. My mother was heartbroken for the girl, and terrified at the possibility that me or my two sisters could be next. From the corners of her heart, she knew it was time for us to leave.

I vividly remember the last day my family was all together in Haiti. We had applied for documentation so we could immigrate to the U.S., but the papers for my sister, B., hadn’t come in yet—so when my mother, brother, other sister and I boarded the plane, B. and my father had to stay behind. My mother was six months pregnant, and, as I watched her absentmindedly rub her stomach, I remember thinking that she looked so full of pain. She buried my sister’s head into the crook of her arms and wiped the tears from B.’s face, repeatedly reminding her that we were not leaving by choice and would call every day. Then, my mother hugged my dad in the way old Caribbean couples do: so conservative in touch but yet so abundant in love. She prayed with my entire family one last time and reminded us that our reunion would not be a matter of if but when.

Dividing our family was the hardest thing we’ve ever had to go through, and I’ve recently come to realize that while leaving was difficult for me, it must have felt nearly impossible for my mother. As I grew up, this part of our family history was quietly off limits—something we had all experienced, but never discussed—but 19 years later, I asked my mother what she went through. What she told me has given my memories an entirely new dimension.

“When we were on the plane, I cried till I didn’t have water left in my body. I felt so much guilt leaving your sister in Haiti. Before even boarding the plane I was already missing her and your father,” my mother told me recently. “When she finally came to Florida, I don’t think I stopped hugging her for hours.”

Currently, Western countries are facing a migrant crisis. Thousands of people are crossing borders, walls and water by any means necessary in the hopes of a future. In Canada alone, just under 50,000 asylum seekers crossed the American/Canadian border last year and that number is only expected to climb. While our Prime Minister has publicly supported refugees, tweeting in 2017, “to those fleeing persecution, terror & war, Canadians will welcome you,” experts have long argued Canadian policies don’t really create safe havens for refugees, asylum seekers, migrants or temporary foreign workers.

“Canadian policies are complicit in ensuring separation of migrant mothers from their children,” says Ethel Tungohan, a York University professor researching migrant labour and immigration. “Policies such as the caregiver program have made it harder for mothers to reunite with their families. Imagine working and living in Canada for years and only doing so with the promise you’ll be reunited with your family, and then finding out you can’t actually [do so].”

As those thousands of people leave their motherlands, I can’t help but think about all the mothers who are being separated from their families and the only lives they’ve known. My mother still dreams vividly of her homeland. She dreams of the palm trees, the sun, the environment, but more than anything, she misses her siblings—some of whom have died since she left. She never got chance to say goodbye.

THE DIVERLUS FAMILY IN 1997 IN HAITI, BEFORE THEY WERE SEPARATED. THE WRITER IS PICTURED IN THE PINK DRESS

The six months my family was separated forever shaped my mother’s life. She longed for my father’s help with the difficulties of her pregnancy, and later when she experienced postpartum depression, which was made even harder by the fact that she was in a new and unknown environment and without a support system. And she yearned for my sister B. After we had all gone to sleep, she cried incessantly in the silence of the night. “It felt like eternity. We talked on the phone every day, but it still wasn’t enough. Every minute felt like days apart. Months felt like years,” she recently told me. “I felt like pieces of me were scattered between Haiti with my daughter and husband and in Florida where I was.”

But she also spent years harbouring guilt and shame for missing time away from my sister. And when we were finally reunited in Miami, Florida, she felt like she had to make up for lost time, making sure she wasn’t missing anymore milestones and moments. “I don’t think I could ever do it again. If I could go back or even if the circumstances somehow were to happen again, I can never imagine leaving your sister. Not for one month, not for a week,” my mother explains as she holds back tears.

My family is one of the lucky ones—we were only separated for six months. But for so many others, years and lifespans pass before they are able to see their loved ones. Migration, while it provides the opportunity for a better life, also inherently means that there is a loss. I think of my grandmother who passed without meeting my younger American-born sisters. I think of my mother who spent 15 years unable to visit her homeland. I think of mothers dreaming of the day their families can be all together in one room. This Mother’s Day is for them.

Canada has an obligation to help Haitians fleeing Trump

Canada has played an active role in the destabilization of the Haitian government by repeatedly infringing on its sovereignty.

Imagine your current country, possibly the only one you’ve ever known, forcibly kicking you out; your home country is unstable and perilous; and upon arrival at your prospect country, you’re arrested, detained, and turned away. To be Haitian is to be trapped in a never-ending game of migrant roulette.

Last month, Donald Trump announced he will be rescinding the temporary protection status (TPS) for Haitians living in the United States. Under TPS, Haitians whose entire worlds were destroyed by the catastrophic 2010 earthquake, which killed more than 200,000 people, and that displaced over 1.5 million people were provided protection and status in the U.S.

This move will result in the deportation of 60,000 people back to an unstable country still recovering from environmental and political assaults; a country many do not know. Many are left with no choice but to emigrate en masse out of the U.S. There are thousands of families, parents, and children crossing the border into Canada, desperate for a home, and just to be met with immigration detention, arrest and deportation.

As with many Trump policies, Canadians are quick to condemn. However, Trump’s assault on the Haitian diaspora is not unlike Trudeau’s actions within our borders. Despite claiming itself as a “safe haven for refugees,” the Canadian government has arrested more than 3,000 Haitians trying to gain asylum in Canada. Canada too, has turned its back on Haitian refugees looking for safety.

Canadians have an ethical obligation to provide refuge and a home for Haitian refugees fleeing persecution from the U.S. government. After all, Canada has played an active role in the destabilization of the Haitian government by repeatedly infringing on its sovereignty. Haitian politicians, such as Jean-Charles Moise, and Haitian newspapers, like Haiti Progrès, have attributed the ousting of Jean-Bernard Aristide as a significant moment.

In 2003, the federal Liberal government organized an assembly of Canadian, American and French leaders to discuss the state of Haiti — with no actual Haitian officials present. There, they decided to stage a coup-d’état, and forcibly oust Haiti’s first democratically elected president, Jean-Bertrand Aristide. Days later, thousands of troops were deployed into Haiti under a false pretense of regional stabilization. This coup would lead to thousands of deaths of Haitian civilians as collateral damage in the name of Canadian peacekeeping.

The Canadian government has a history of utilizing military intervention — often backed by the United Nations — to meddle in Haiti’s political climate. Canada’s imperial fingerprints can be traced through law enforcement and foreign aid. Following the coup, Canada actively remilitarized the Haitian police. Following the earthquake, Canada deployed 2,000 troops to the island initially sent as search and rescue, but overstayed their welcome and actively impeded on Haitian people’s ability to live life freely.

As foreign nations’ interests in Haiti increases, the country destabilizes. Since the 1970s, Haiti’s unstable climate has created several waves of mass migration of Haitians into the U.S. and Canada. My family experienced both ends of the migration route, first landing in the U.S. and later relocating to Canada. For more than 50 years, families have been forced to migrate, endure decades-long family separation, and navigate varying precarious immigration status. To be Haitian is to feel stateless.

The impacts of Canada’s imperial relationship with Haiti are long lasting. We must grapple with the reality that our foreign policy and military interests have contributed to Haiti’s political and economic instability. It is time for Canadians to take responsibility for our complicity and its impacts on Haitians living in Haiti and the diaspora. It is time for Canadians to welcome Haitian migrants seeking refuge here with open arms; after all, we never extended that courtesy when we barged in and occupied their land.

In less than 19 months, thousands will suddenly lose their legal status and likely targeted, detained, and forcibly removed from the U.S. As the inevitable panic sets in, more will attempt to come to Canada. From January to September this year alone, 6,360 Haitians applied for asylum in Canada; with only 10 per cent being approved for status. Canada should live by its promise to being a welcoming space for refugees and open its door to the tens of thousands fleeing Trump’s persecution.

Police oversight recommendations are out: It’s your move Kathleen Wynne

Black Lives Matters Toronto says the Tulloch review offers many positive and required changes, but in some areas it doesn’t go far enough.

Black Lives Matters Toronto says the Tulloch review offers many positive and required changes, but in some areas it doesn’t go far enough.

A year ago, Black Lives Matter Toronto concluded #BLMTOtentcity, our 15-day occupation of Toronto Police headquarters. Braving volatile weather and a police raid, our people demanded justice for Andrew Loku and an overhaul of the Special Investigations Unit.

Twenty-seven years ago, black activists pushed for civilian oversight of the police. The SIU was created, and lauded as the provincial police watchdog, with a mission to “nurture public confidence in policing by ensuring that police conduct is subject to rigorous and independent investigations.”

On paper, this makes sense. And while the agency was initially welcomed by our elders, reality and time have painted a different picture. The SIU matured into a secretive agency of ex-officers, who make it easier for current officers to act with impunity.

Under the SIU’s watch, there has been a dearth of police officers charged and barely any convicted. Of 3,400 investigations, 95 have had criminal charges laid (less than 3 per cent), 16 have led to convictions, and only three have served time.

Take that in.

The demand to overhaul the SIU came after three decades of the SIU failing Ontarians and instead absolving police officers of their actions. The province listened and ordered an Independent Police Oversight Review, led by Justice Michael Tulloch.

Last week, the review released 129 recommendations. Most of them are what our communities have been calling on for years, including the public release of all past and future reports, demographic-based data on victims of police violence, and victims support services. These recommendations are the result of decades-long activism. These recommendations are the result of #BLMTOtentcity.

Some of these recommendations would represent important steps forward, if adopted. But some just don’t go far enough.

The report recommends that at least 50 per cent of the nonforensic investigators on an investigative team should have no background in policing. This threshold will continue to bring to question the integrity and impartiality of the agency’s investigations. Let’s be real: 50 per cent of investigators being former cops is a lot of influence. The province needs to go over and above this recommendation and any former or current police officer should be ineligible to serve on the SIU.

The premier should also take the bold step of committing to release the names of police officers investigated by the SIU, a step the report fails to recommend. The report considers the question and concludes that the standard for police should be the same as the standard for civilians alleged to have committed a crime; their names are released after an initial investigation and charge.

But this fails to acknowledge the simple fact that police officers are not civilians. They should be held to a higher standard. What if the officer has a history of excessive force, or targeting black communities? What is there to hide? Why shouldn’t we know who’s hurting civilians? After all, we employ them. Our tax dollars support their inflated salaries and the weapons they use to terrorize our communities.

The question remains, would publicizing the names of officers who harm decrease the number of misconduct cases? We think so. Officers who shoot, kill, and sexually assault civilians should do so with the knowledge the public will be apprised of the details; that is a tenet of accountability. These are public officials working in official capacity.

The report is a much-needed first step, but simply, we need more.

In the past 30 years, there have been at least seven reviews that speak directly to police accountability and the SIU, going as far back as the 1988 Task Force on Race Relations and Policing.

They’ve produced similar results: promises of wide-sweeping changes, public fervour, and years of piecemeal action by policy-makers. Knowing history’s knack for repeating itself, Ontarians should be cautious in their optimism.

These are recommendations to fix a system predicated on stacking the cards in favour of trigger-happy cops, and this report is only as useful as its swift implementation by the province. Recommendations are nice but they mean nothing without action. Families of slain black people will not get justice from a report that sits on a shelf collecting dust.

On the last day of #BLMTOtentcity, Kathleen Wynne met with protestors outside and made fervent promises of commitment to addressing anti-black violence at the institutional level. Wynne, the ball is in your court. The work has only begun.

Don’t Call Me A Social Justice Warrior (Seriously, don’t.)

Itwas the third class of my intro to journalism class in my first year. It was one of those classes that relied solely on participation marks and the quizzes taken at the end of the class, so everyone showed up just to sleep in the theatre-style seats.

Full disclosure: Pascale is a Toronto based activist and writer, and co-founder of Black Lives Matter Toronto.

It was the third class of my intro to journalism class in my first year. It was one of those classes that relied solely on participation marks and the quizzes taken at the end of the class, so everyone showed up just to sleep in the theatre-style seats.

Three weeks into my undergrad career, and I was already frustrated with the lack of critical classes we were offered. Where are the classes that talk about race, class, gender and sexuality in journalism? Instead we were spoon-fed and regurgitated the same politics that is seen in mainstream journalism, without the analysis.

Mainstream journalism is filled with half-truths that are much easier to digest. Mainstream journalism only shows one side.

In this class, every week the professor brought in a guest speaker, and this week’s guest was a journalist recounting an interview she had done for an article. In the middle of her story, she began to mock the accent of the East Asian person she had interviewed. While some of the class giggled, I was mortified. I couldn’t believe the lack of awareness and better judgement that this journalist displayed. I was even more mortified to see our professor laughing along.

One brave student raised her hand and asked the guest not mock the accent, which closely resembled that of her mom, family and community. The student called out the racist undertones, and felt like it was a personal attack on herself and her family. Before the guest lecturer could even respond, our professor took the mic, and said, “Obviously this isn’t racist, please don’t be a social justice warrior.”

I walked out of the class at that moment and never returned.

obviously this isn’t racist, please don’t be a social justice warrior

That was the first time I’d ever heard the term “social justice warrior.” That was the first moment I heard someone trying to put another down for standing up for what they believed in.

Tun Nyi Soe

This term is more often thrown at people advocating for feminism or against racism. As I started to invest in social justice, specifically fighting against anti-black racism, the term warrior justice got thrown at me regularly. I know and realize the term “social justice warrior” is an attempt to silence me. It comes from people who are too lazy, unmotivated or simply unwilling to change oppressive behaviours and languages that often target the most marginalized in our societies.

From my understanding, the term social justice warrior thinks that the things we are talking about are solely theoretical. When we talk about rape culture for instance, the unaware think it’s an irrational fear inside our minds to disown or call out men. When we talk about these issues they think it’s merely just a political conversation. Rather, when we talk about rape culture it’s about my individual life and experiences being shaped by misogyny since childhood — the reality of living a life fearful of violence happening not only to myself but also my three sisters, my mom and everyone I know.

This goes for varied topics of oppression. When we call out the use of a derogatory word or term, that is us, the marginalized, standing up for our dignity and our right to exist without an attack on our personhood.

Paigelina

The term social justice warrior is an attempt to devalue me, and anyone that carries the hope of creating an equitable world.

The term “warrior” however is the perfect word to describe us. To be able to live in a state of consciousness takes a warrior. To be able to fight for yourself and your community takes a warrior — but to be both able and willing to make your oppressor see the ways in which they are oppressing you takes so much more than a warrior: it takes an activist.